"Kansas" - from The United States Illustrated, 1855 | Mark Twain’s Mississippi |NIU Digital Library

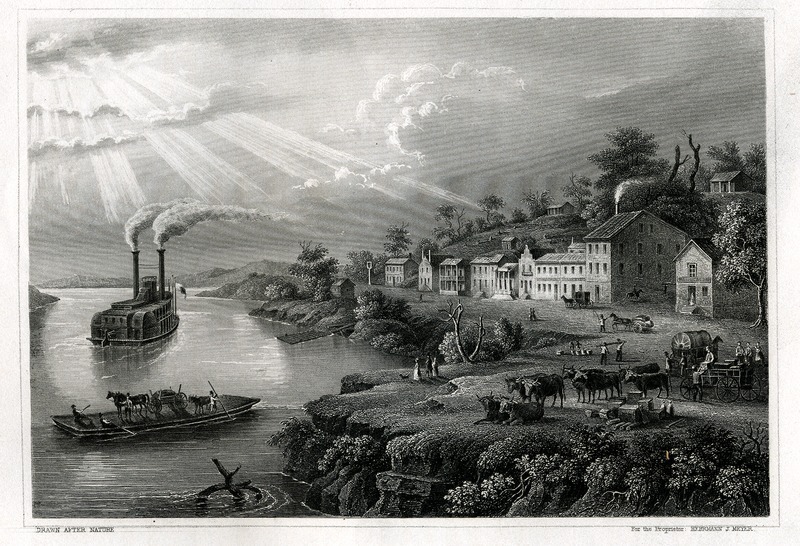

This 1855 illustration depicts an idyllic scene in Kansas, most likely along the Kansas River. In this period Kansas was anything but idyllic, however. Kansas became a territory with the implementation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act on May 30, 1854. The act, which left occupants of the Kansas and Nebraska territories seeking statehood to decide if human slavery would exist in their jurisdiction, set aside the Missouri Compromise of 1820, by which Congress had sought to maintain a rough balance between slave and free states in the Union by restricting the former to territory south of the 36 30′ parallel, excluding Missouri itself. Pro- and anti-slavery settlers poured into Kansas, many with the explicit goal of establishing their preferred policy there. Political controversy ensued.

Pro-slavery settlers dominated the initial territorial legislature elected on March 30, 1855. This body would determine if Kansas would enter the Union as a slave or free state. Opponents of slavery around the Union argued that widespread voter fraud made the election’s results illegitimate, and the territorial governor invalidated results in several districts. New elections gave anti-slavery settlers greater representation, but they remained in a decided minority.

The United States Congress sent a special committee to Kansas, which concluded that the territorial legislature was an illegally constituted body without authority. The territorial legislature convened in spite of the finding, rejected the credentials of those who had won the new elections, and passed laws paving the way for Kansas to enter the Union as a slave state. Anti-slavery Kansans rejected this government and formed their own, which in January, 1856, President Franklin Pierce declared illegal. Violence broke out between pro- and anti-slavery settlers, resulting in the shooting death of a free stater near Lawrence in December of 1855.

Political controversy produced physical violence. On May 21, 1856, pro-slavery forces stormed Lawrence, destroying a hotel and two newspaper offices, and sacking homes and businesses. Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts soon delivered a speech on the Senate floor depicting pro-slavery views and actions as akin to the rape of a virgin. Sumner’s speech especially singled out the South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler for criticism. The next day Butler’s cousin, the South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks, attacked Sumner on the Senate floor with a cane, inflicting grave injuries.

In Kansas, the anti-slavery activist John Brown led his sons and other followers to murder five pro-slavery settlers at Pottawatomie Creek on May 24, 1856. On the Fourth of July President Pierce sent U.S. Army troops to remove the Free State Legislature at Topeka. In August pro-slavery forces burned the Free State town of Osawatomie, Kansas after driving off defenders led by Brown. The last major outbreak of violence occurred in the Marais des Cygnes massacre of 1858, in which pro-slavery forces killed five Free State men. In all, approximately 56 people died in “Bleeding Kansas” in the years before the Civil War began.